Translate

Translate

-

* News

- - Agira 2018, 75 years later

- - Agira 2013, 70 years later

- - Gallery of ceremony 2013

- - Operation Husky 2013

- * Students' Contribute

- * About Us

- * Visitor's Book

- * Collaborators

- * Canadian Battles

- * Italian Defensive Positions

- * Allied Forces

- * Historical Movies

- Historical Information

- Historical Maps

- * Bibliography

- Biographies

- * Catania War Cemetery

- * Moro River War Cemetery

- * Syracuse War Cemetery

The first 10 days of the Battle of Sicily had been relatively easy for the Canadians; resistance by German and Italian soldiers generally consisted of rear-guard actions. The 1st Division continued its advance on 19 Jul by having the 2nd Brigade pass through recently taken Valguarnera. Progress was slow, owing to extensive enemy demolition of bridges and cratering of roads, and the advance was largely done on foot. Enemy snipers, machine guns and mortar fire all were used to harass the Canadians. Their immediate objective - a crossroads 5 miles to the north of Valguarnera - was not taken until late afternoon.

The countryside was growing more forbidding. Hills were now giving way to mountains; in the distance the troops could for the first time see Etna, the majestic, snow-capped volcano, forty miles to the northeast. None of these footsore Canadians could know that seventeen days of bitter fighting lay ahead.1

Leonforte and Assoro were the next objectives.

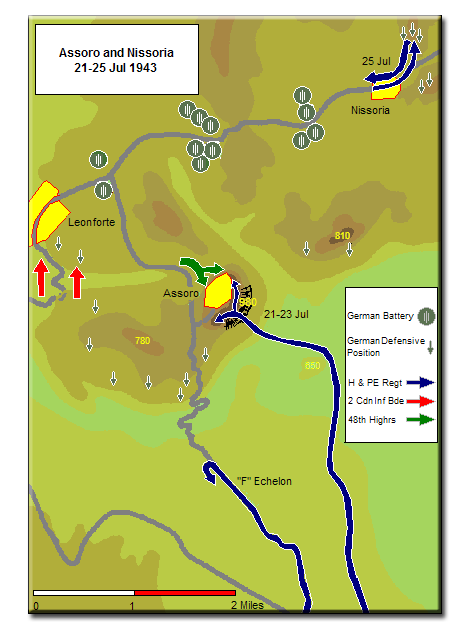

Assoro was the highest point for miles in any direction, and Leonforte sat astride Route 121, the main east-west highway on the island linking Palermo and Catania. The 1st Brigade was tasked with Assoro while the 2nd Brigade was ordered to take Leonforte. The two attacks began at midnight and into the early hours of 20 Jul.

Assoro was the highest point for miles in any direction, and Leonforte sat astride Route 121, the main east-west highway on the island linking Palermo and Catania. The 1st Brigade was tasked with Assoro while the 2nd Brigade was ordered to take Leonforte. The two attacks began at midnight and into the early hours of 20 Jul.

July 20, 1943 brought 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade up against a major obstacle in Sicily - the 906-metre high summit of Monte Assoro.

Monte Assoro dominated all routes that 1st Canadian Infantry Division needed to continue advancing by. The Germans had transformed it into a defensive bastion.

The bulk of Panzergrenadier Regiment 104, under Oberstleutnant Ens, held Leonforte, with a small detachment at Assoro numbering about 100 men of a company-sized detachment, supported by 5 tanks.3

A large battle ensued as the 1st Brigade attempted to cross the Dittaino River. The river itself was dry, but the dry river bed was an obstacle to vehicles, and the river valley was under observation from Germans on the heights opposite. "The First Brigade soon encountered trouble which culminated in its biggest battle to date." The 48th Highlanders managed to secure a crossing, but when the Royal Canadian Regiment passed through with Sherman tanks of the Three Rivers Regiment, nine vehicles were lost to mines, and accurate fire from the heights of Assoro four miles away stopped the advance cold. "In these circumstances, movement during daylight was impossible."2

A cliff 1000 feet high with an ancient castle overlooked the countryside, with the only road to the town (founded in 1000 BC and clinging to the western slopes of the hill, below the summit) rising in hairpin turns; the loss of nine tanks to mines suggested the road would not be an inviting route.

Brigadier Howard Graham assigned Monte Assoro’s capture to Ontario’s Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment. Graham realized the road would be covered by countless machine-gun and sniper positions and was exposed to artillery and mortar fire. To hope for success by moving up the torturous road was out of the question,” he said. “The regiment would be slaughtered.”

Graham and  Lieutenant Colonel Bruce Sutcliffe, commander of the Hasty Ps, decided the only chance was to carry out a right hook up the summit’s virtually sheer southeast face by following “what appeared to be goat tracks in some places.” Worse came to worse, the regiment would just have to scale it. The assault would have to take place under cover of darkness. The troops must gain and capture the summit before dawn or end up easy targets for the German defenders. The assault teams would carry minimal gear - weapons, ammunition, and precious water bottles.

Lieutenant Colonel Bruce Sutcliffe, commander of the Hasty Ps, decided the only chance was to carry out a right hook up the summit’s virtually sheer southeast face by following “what appeared to be goat tracks in some places.” Worse came to worse, the regiment would just have to scale it. The assault would have to take place under cover of darkness. The troops must gain and capture the summit before dawn or end up easy targets for the German defenders. The assault teams would carry minimal gear - weapons, ammunition, and precious water bottles.

No sooner was this decision taken than Sutcliffe was killed by German artillery from a slit trench too small for them.

Like the Seaforths at Leonforte, casualties to the battalion headquarters group of the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment were suffered on the 20th.

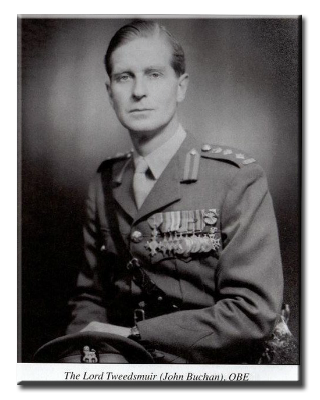

Regimental command passed to  Major John Tweedsmuir - a British lord (son of the former Governor-General) posted to the Hasty Ps. Tweedsmuir hurriedly organized the attack and the troops moved off at 21.30 hours. Leading the way was a special assault company of hand-picked men under Captain Alex Campbell.

Major John Tweedsmuir - a British lord (son of the former Governor-General) posted to the Hasty Ps. Tweedsmuir hurriedly organized the attack and the troops moved off at 21.30 hours. Leading the way was a special assault company of hand-picked men under Captain Alex Campbell.

It consisted of about sixty men broken into three platoons of twenty each. Among the platoon leaders was Lieutenant Farley Mowat.

The battalion was divided into two groups; the assault company and one rifle company were to scale the left shoulder of the hill, and the new Commanding Officer Lord Tweedsmuir took the remainder of the battalion to the north-east - finding a goat track and passage to the top.

The assault company, leading the Hasty Ps set off single file into the darkness. Because of the difficult terrain it was not until 04.00 hours that they reached the summit's base. Campbell's men led the way up the cliff face. Centuries before, the mountain had been sculpted into forty-seven steep, now badly overgrown terraces. The men moved up ledge to ledge, passing weapons and ammunition up to those leading, and then clawing their way up. It was gruelling work. Yet not a man slipped and fell. Not a rifle clattered against stone to betray them.

The approach march began at dusk and it was the most difficult forced march the Regiment ever attempted, in training or in war. The going was foul; through a maze of sheer-sided gullys, knife-edge ridges and boulder-strewn water courses. There was the constant expectation of discovery, for it seemed certain that the enemy would at least have listening posts on his open flank. Absolute silence was each man's hope of survival - but silence on that nightmare march was almost impossible to maintain...

The approach march began at dusk and it was the most difficult forced march the Regiment ever attempted, in training or in war. The going was foul; through a maze of sheer-sided gullys, knife-edge ridges and boulder-strewn water courses. There was the constant expectation of discovery, for it seemed certain that the enemy would at least have listening posts on his open flank. Absolute silence was each man's hope of survival - but silence on that nightmare march was almost impossible to maintain...

There was a desperate urgency in that march for there were long miles to go, and at the end, the cliff to scale before the dawn light could reveal the Regiment to the enemy above. A donkey, laden with a wireless set, was literally dragged forward by its escort until it collapsed and died. The men went on.

By 04.00 hours the assault company had scaled the last preliminary ridge and was appalled to find that the base of the mountain, looming through the pre-dawn greyness, was still separated from it by a gully a hundred feet deep, and nearly as sheer as an ancient moat. It was too late to turn back. Men scrambled down into the great natural ditch, crossed the bottom, and paused to draw breath. First light was just an hour away. Under the soldiers' hands were the cliff rocks towering a thousand feet into the dark skies.

Each man who made that climb performed his own private miracle. From ledge to ledge the dark figures made their way, hauling each other up, passing along their weapons and ammunition from hand to hand. A signaller made that climb with a heavy wireless set strapped to his back - a thing that in daylight was seen to be impossible. Yet no man slipped, no man dropped so much as a clip of ammunition. It was just as well, for any sound by one would have been fatal to all.4

Shortly before dawn, the assault company crested the hill and managed to take the summit from unsuspecting sentries without losing a single man. Believing the cliff impossible to scale, the Germans had concentrated their forces overlooking the road.

A wild melee ensued that the Hasty Ps won in a fierce day of fighting.

Commanding high ground above the town, the Germans were placed in an untenable position, with Canadian fire also knocking out eight vehicles of an approaching Axis convoy. German artillery fire lifted from Leonforte to drop on Assoro.

Unlike the case in other actions, radio communication managed to hold, and accurate artillery support (aided by a former artilleryman among the Hasty P's as well as a captured 20-power German scissors binocular) was played against German batteries.

For several hours thereafter the Hastings, clinging to their exposed position on the mountain top, the rocky nature of which prevented the digging of effective slit trenches, were subjected to intermittent mortar and artillery fire. Enemy snipers in Assoro were also a constant hazard; nevertheless, casualties were surprisingly light.5

Monte Assoro no longer impeded the Canadian advance. Only eight Hasty Ps died in an action Canadian Press correspondent Ross Munro declared "the most daring and spectacular...of all the actions in Sicily."

An enemy counterattack from the town in the late afternoon advanced almost to the top of the hill, but was beaten back with accurate artillery fire. The Canadians received their first exposure to fire from the German Nebelwerfer, a rocket launcher whose projectiles made such a demoralizing shriek while in flight that they were known as "Moaning Minnies".

The regiment held on during the night, but no food other than emergency rations had been brought up. An emergency carrying party of 100 men from the Royal Canadian Regiment brought food and supplies on the morning of 22 Jul. The regiment's support weapons were another story, and "F" Echelon vehicles of the Hasty P's had been ambushed in the early morning of 21 Jul when both they and the Germans realized they had stopped for the night in too close to each other for comfort.

As the RCR carrying party brought logistic relief to the Hasty P's on the morning of 22 Jul, the 48th Highlanders brought tactical relief by attacking from the west of Assoro, driving the enemy from the south-western approach to the town and allowing the 1st Field Company, RCE (and 100 POWs) to fill craters and allow the passage of tanks of the Three Rivers Regiment. A link-up between the Highlanders and Hasty P's was effected by noon of Jul 22.

No decorations were awarded for Assoro, but the Canadians earned praise from friend and foe alike. An often quoted German after action report praised the Canadians for their fieldcraft.

Good soldier material. English and Canadians harder in the attack than the Americans. In general fair ways of fighting. In fieldcraft (Indianerkrieg) superior to our own troops. Very mobile at night,surprise break-ins, clever infiltrations at night with small groups between our strong points.

The entire report is available in the German After Action Reports - Sicily article.

While the battle is often described in superlative terms by Canadian historians; Farley Mowat's assessment in his history of the Hasty P's seems the most balanced.

While it was no great victory in terms of casualties inflicted on the enemy, Assoro was nevertheless a spectacular triumph of endurance and initiative, and the spirit of the men, subdued temporarily by their first baptism of heavy shell-fire, now rose to unprecedented heights.6

The next objectives for the Division lay 20 miles to the east, on the Salso River, however, the RCR were bloodily stopped at Nissoria just 5 miles from Assoro, along with the loss of several supporting tanks. The Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment was thrown in next without tank or artillery support; the cover of darkness did not make up for the lack of reconnaissance and this attack was also stopped. The Hasty P's left the field with 69 dead and wounded inflicted on them. A third attack by the 48th Highlanders did no better, and it was not until a co-ordinated attack by the 2nd Brigade with artillery support was launched that Nissoria fell.

The following Canadian units were awarded the Battle Honour "Assoro" for participation in these actions:

![]() 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade

1st Canadian Infantry Brigade

-

The 48th Highlanders of Canada

-

The Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment

-

Dancocks, Daniel G. D-Day Dodgers: The Canadians in Italy 1943-1945 (McClelland & Stewart Inc., Toronto, ON, 1991) ISBN 0771025440 pp.60-61

-

Ibid, p.61

-

Mitcham, Samuel and Friedrich von Stauffenberg The Battle of Sicily: How the Allies Lost Their Chance for Total Victory (Orion Books, New York, NY, 1991), p.192

-

Mowat, Farley. The Regiment (McClelland & Stewart Inc., Toronto, ON, 1955) ISBN 0771066945 p.116-117 (paperback edition)

-

Nicholson, Gerald. Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War. Volume II: The Canadians in Italy, 1943-1945 (Queen's Printer, Ottawa, ON, 1957) p.105

-

Mowat, Ibid, p.125